Introduction

The internet, as we know it, has reached a critical juncture. For decades, the digital world has relied on IPv4 (Internet Protocol version 4), a system designed in the early days of the ARPANET with a capacity of approximately 4.3 billion unique addresses. While this seemed inexhaustible in the 1980s, the explosion of the Internet of Things (IoT), mobile devices, **Cloud Networking**, and the ubiquity of **Remote Work** has completely depleted the available pool of IPv4 addresses. The solution is IPv6, a 128-bit addressing scheme that provides an exponentially larger address space, enhanced security features, and streamlined packet processing.

The transition to IPv6 is not merely about adding more numbers; it is a fundamental upgrade to **Network Architecture**. Modern Internet Service Providers (ISPs), including satellite internet providers and fiber networks, are increasingly provisioning large IPv6 blocks (such as /38 or /48 prefixes) to regions previously underserved. This shift allows for dedicated IP addresses for end-users, eliminating the need for Carrier-Grade NAT (CGNAT). The result is a tangible improvement in **Network Performance**, reduced **Latency**, and a more robust infrastructure for **Digital Nomads** and **Travel Tech** enthusiasts who rely on stable connections globally. This article provides a comprehensive technical deep dive into IPv6, covering core concepts, implementation strategies, and advanced **Network Engineering** practices.

Section 1: Core Concepts and Addressing Architecture

At the heart of **Computer Networking**, the Internet Protocol acts as the delivery mechanism for packets across boundaries. IPv6 differs significantly from IPv4 in its header structure and addressing methodology. While IPv4 uses a 32-bit address represented in dotted-decimal notation (e.g., 192.168.1.1), IPv6 utilizes a 128-bit address represented in hexadecimal (e.g., 2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334).

The IPv6 Header and Packet Structure

The IPv6 header is streamlined to improve processing efficiency on **Network Devices** like **Routers** and **Switches**. Unlike the variable-length IPv4 header, the IPv6 header has a fixed length of 40 bytes. This simplification allows hardware to process packets faster, reducing processor overhead. Key fields include:

* **Traffic Class:** Similar to Type of Service (ToS) in IPv4, used for QoS (Quality of Service).

* **Flow Label:** A new field that allows labeling of sequences of packets for special handling by routers, crucial for real-time applications like VoIP and video streaming.

* **Next Header:** Indicates the type of header immediately following the IPv6 header (e.g., **TCP/IP** or UDP).

Addressing and Notation

IPv6 addresses are divided into eight groups of four hexadecimal digits, separated by colons. To make these long addresses manageable for **System Administration**, specific compression rules apply:

1. Leading zeros in a group can be omitted.

2. One or more consecutive groups of zeros can be replaced by a double colon (::), but this can only occur once per address.

Understanding how to programmatically manipulate these addresses is essential for **Network Automation** and **DevOps Networking**.

import ipaddress

def analyze_ipv6(address_str):

try:

# Create an IPv6 object

ipv6_addr = ipaddress.IPv6Address(address_str)

print(f"Original: {address_str}")

print(f"Compressed: {ipv6_addr.compressed}")

print(f"Exploded: {ipv6_addr.exploded}")

print(f"Is Global? {ipv6_addr.is_global}")

print(f"Is Link-Local? {ipv6_addr.is_link_local}")

print(f"Is Multicast? {ipv6_addr.is_multicast}")

# Calculate the reverse pointer for DNS Protocol

print(f"Reverse Pointer: {ipv6_addr.reverse_pointer}")

except ipaddress.AddressValueError:

print(f"Invalid IPv6 Address: {address_str}")

# Example Usage

analyze_ipv6('2001:0db8:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334:0001')

analyze_ipv6('fe80::1') # Link-local exampleAddress Types

In the **OSI Model** context, specifically the **Network Layer**, IPv6 introduces distinct address types:

* **Unicast:** Identifies a single interface. A packet sent to a unicast address is delivered to the interface identified by that address.

* **Multicast:** Identifies a set of interfaces. A packet sent to a multicast address is delivered to all interfaces in the set. This replaces IPv4 Broadcast, significantly reducing network noise.

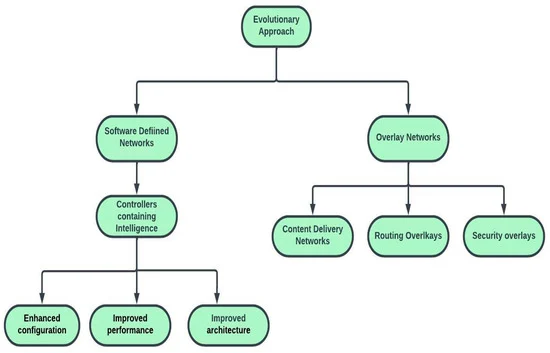

* **Anycast:** Identifies a set of interfaces (usually on different nodes). A packet is delivered to the nearest interface as determined by routing protocols. This is vital for **CDN** (Content Delivery Network) performance and **DNS Protocol** redundancy.

Section 2: Implementation Details and Network Design

Implementing IPv6 requires a shift in **Network Design** thinking, particularly regarding **Subnetting** and **CIDR** (Classless Inter-Domain Routing). In IPv4, subnetting was often about conserving addresses. In IPv6, the address space is so vast that subnetting is organized hierarchically for routing efficiency and management.

Subnetting and Prefix Delegation

The standard subnet size for a LAN is a /64, which provides $2^{64}$ host addresses. This is mandated for features like SLAAC (Stateless Address Autoconfiguration) to function correctly. ISPs typically assign a /48 or /56 to enterprise customers and, increasingly, /64 or even /60 to residential users. In scenarios involving large-scale deployments, such as satellite internet provisioning for a city, a /38 might be allocated to a gateway, which is then carved up into smaller prefixes for users.

This abundance of addresses eliminates the need for NAT. Every device can have a global public IP address. This restores the end-to-end principle of the internet but requires robust **Network Security** measures, specifically stateful **Firewalls**, to protect devices that are now directly addressable.

Socket Programming and Dual-Stack

During the transition period, most networks run “Dual-Stack,” supporting both IPv4 and IPv6 simultaneously. For **Network Programming**, developers must ensure their applications can handle IPv6 sockets. Modern **Network Libraries** in languages like Python, Go, and Node.js handle this seamlessly, but understanding the underlying **Socket Programming** is crucial.

Here is an example of creating a dual-stack compatible server using Python. This is relevant for **Web Services** and **Microservices** architectures.

import socket

import sys

def start_dual_stack_server(port=8080):

# Create a socket that can handle IPv6

# AF_INET6 is the address family for IPv6

# SOCK_STREAM indicates TCP

try:

sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET6, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

except OSError as e:

print(f"Socket creation failed: {e}")

return

# Set socket option to allow IPv4 mapped addresses

# This allows the socket to accept both IPv4 and IPv6 connections

# if the OS supports dual-stack sockets by default (common in Linux)

try:

sock.setsockopt(socket.IPPROTO_IPV6, socket.IPV6_V6ONLY, 0)

except AttributeError:

print("System does not support IPV6_V6ONLY socket option")

try:

# Bind to the wildcard address '::' which covers all interfaces

sock.bind(('::', port))

sock.listen(5)

print(f"Server listening on port {port} (Dual Stack)")

while True:

conn, addr = sock.accept()

# addr will be a tuple. For IPv6: (host, port, flowinfo, scopeid)

print(f"Connected by {addr}")

data = conn.recv(1024)

if data:

response = b"HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\nContent-Type: text/plain\r\n\r\nHello from IPv6!"

conn.sendall(response)

conn.close()

except Exception as e:

print(f"Server error: {e}")

finally:

sock.close()

if __name__ == "__main__":

start_dual_stack_server()SLAAC vs. DHCPv6

IPv6 introduces SLAAC, allowing hosts to generate their own addresses using the network prefix advertised by the router and their own MAC address (EUI-64) or a random number (privacy extensions). This reduces the burden of **Network Administration**. However, for strict control over address assignment and DNS server distribution, DHCPv6 is still used in enterprise environments.

Section 3: Advanced Techniques and Security

As organizations adopt **Software-Defined Networking (SDN)** and **Network Virtualization**, IPv6 plays a pivotal role. The massive address space facilitates flat network designs, essential for **Kubernetes** clusters and **Service Mesh** implementations where pods require unique IPs.

Routing Protocols and Packet Analysis

Routing in IPv6 is handled by updated protocols such as OSPFv3 and MP-BGP (Multiprotocol BGP). These protocols are designed to handle the larger address sizes and distinct extension headers. For **Network Troubleshooting**, tools like **Wireshark** and `tcpdump` are indispensable. Analyzing IPv6 traffic often involves looking at ICMPv6, which is far more critical in IPv6 than ICMP was in IPv4. ICMPv6 handles Neighbor Discovery Protocol (NDP), which replaces ARP (Address Resolution Protocol).

Below is a Python script using the `scapy` library, a powerful tool for **Packet Analysis** and **Network Security** testing. This script crafts an IPv6 ICMP Echo Request (Ping) and analyzes the response, useful for **Network Monitoring**.

from scapy.all import *

from scapy.layers.inet6 import IPv6, ICMPv6EchoRequest

def ipv6_ping_analysis(target_ip):

print(f"Sending IPv6 Echo Request to {target_ip}...")

# Craft the packet

# IPv6 Header -> ICMPv6 Header

packet = IPv6(dst=target_ip)/ICMPv6EchoRequest()

# Send and receive

# sr1 sends a packet and waits for a single response

reply = sr1(packet, timeout=2, verbose=0)

if reply:

print(f"Reply received from: {reply.src}")

# Analyze Hop Limit (TTL in IPv4)

print(f"Hop Limit: {reply.hlim}")

# Check Traffic Class

print(f"Traffic Class: {reply.tc}")

if reply.haslayer(ICMPv6EchoReply):

print("Status: Target is Alive (Echo Reply received)")

else:

print("Status: Received packet, but not Echo Reply")

reply.show() # Show packet details for debugging

else:

print("No reply received. Host may be down or filtering ICMPv6.")

# Note: This requires root/admin privileges to run

# Example target: Google's Public DNS

# ipv6_ping_analysis("2001:4860:4860::8888")Security Considerations

While IPv6 was designed with security in mind (IPsec support is mandatory in the architecture, though optional in implementation), it introduces new attack vectors.

1. **Reconnaissance:** Scanning a /64 subnet is computationally impossible, preventing brute-force scanning. However, attackers now focus on DNS enumeration and public log analysis.

2. **Extension Headers:** Attackers can manipulate extension headers to bypass firewalls or cause Denial of Service (DoS).

3. **NDP Attacks:** Without proper security (like SEND – Secure Neighbor Discovery), local attackers can spoof routers or neighbors.

**Network Engineers** must configure **Firewalls** to filter specific extension headers and enforce strict policies on ICMPv6 types allowed (e.g., allowing Packet Too Big for MTU discovery, but blocking others).

Section 4: Best Practices and Optimization

To ensure optimal **Bandwidth** usage and minimal **Latency**, especially for high-demand applications like **Travel Photography** uploads or **Edge Computing**, proper configuration is key.

Network Configuration with CLI

For **System Administration** on Linux servers, the `ip` command suite is the standard. The legacy `ifconfig` is largely deprecated. Below is a practical example of configuring an IPv6 address and route manually, which is often required in **Network Virtualization** environments or custom **VPN** setups.

#!/bin/bash

# Define Interface and Address

INTERFACE="eth0"

IPV6_ADDR="2001:db8:1234:1::10/64"

GATEWAY="2001:db8:1234:1::1"

echo "Configuring IPv6 on $INTERFACE..."

# 1. Enable IPv6 on the interface (usually on by default)

sysctl -w net.ipv6.conf.$INTERFACE.disable_ipv6=0

# 2. Add the IPv6 Address

# 'ip -6 addr add' is the command

# 'dev' specifies the device

sudo ip -6 addr add $IPV6_ADDR dev $INTERFACE

# 3. Add the Default Gateway

# 'via' specifies the next hop

sudo ip -6 route add default via $GATEWAY dev $INTERFACE

# 4. Verify Configuration

echo "Verifying Address:"

ip -6 addr show dev $INTERFACE

echo "Verifying Routing Table:"

ip -6 route show

# 5. Test Connectivity

# ping6 is often an alias for ping -6

ping -6 -c 4 2001:4860:4860::8888DNS and Performance

**DNS Protocol** configuration is critical. An AAAA record maps a hostname to an IPv6 address. To optimize performance, ensure that your **Load Balancing** strategies and **CDN** configurations prioritize IPv6. Many modern operating systems utilize “Happy Eyeballs” (RFC 8305), an algorithm that attempts IPv4 and IPv6 connections in parallel (with a slight preference for IPv6) and uses the first one that connects. This ensures that if an IPv6 path has higher latency or is broken, the user experience doesn’t suffer.

API Design and Web Services

When designing a **REST API** or **GraphQL** endpoint, ensure your logging and rate-limiting logic can handle IPv6. A common pitfall in **API Security** is rate-limiting based on IP address. If you rate-limit a /64 subnet as a single user (thinking it’s like a single IPv4 address), you might block an entire office building. Conversely, if you treat every single IPv6 address as unique, an attacker with a /64 block can rotate through $2^{64}$ addresses to bypass rate limits. The best practice is to rate-limit based on the /64 prefix for residential/mobile networks.

Conclusion

The transition to IPv6 is no longer an option; it is a necessity for the continued growth and stability of the internet. From enabling the massive scale of **IoT** to providing **Digital Nomads** with reliable, dedicated connectivity via next-generation satellite networks, IPv6 is the backbone of modern communication.

For **Network Engineers**, **DevOps** professionals, and **Software Developers**, mastering IPv6 addressing, **Socket Programming**, and security implications is critical. By moving away from the constraints of NAT and IPv4, we open the door to a more transparent, efficient, and secure internet. As adoption grows, driven by lowered costs and improved service quality in emerging markets, the “next generation” protocol is rapidly becoming the current standard. The time to audit your **Network Infrastructure**, update your **Firewalls**, and refactor your code for full IPv6 support is now.