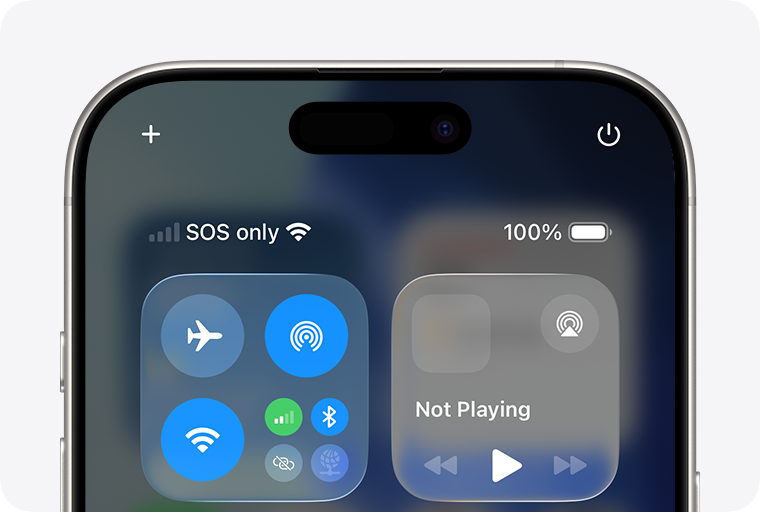

Stop assuming the network is reliable. I see this mistake in code reviews every single week. We build applications on gigabit fiber in our offices, test them on stable Wi-Fi, and then wonder why they crash when a user is on a train moving between cell towers. The reality of 2025 is that while we are pushing toward 6G speeds, the safety net is vanishing. With major carriers finally pulling the plug on 3G infrastructure to free up spectrum for 4G and 5G expansion, the “slow but steady” fallback layer is gone. If your application drops from a high-speed connection, it might not degrade gracefully anymore—it might just hit a dead zone.

I want to talk about how we, as engineers working in Network Development, need to fundamentally change how we handle connectivity in our code. We can’t just rely on TCP retransmissions to save us. We need application-layer awareness of the underlying network topology.

The Death of the Fallback Network

For the last decade, my strategy for mobile reliability was simple: optimize for 4G, but ensure the handshake works on 3G. That logic is obsolete. I’m seeing a massive shift in Network Architecture where legacy protocols are being aggressively sunset. When a user leaves a 4G coverage area now, they aren’t dropping to 3G; they are often facing a hard disconnect or a chaotic handover to a different band.

This impacts how we handle socket programming. Standard timeouts are too dumb for this environment. If I’m building a real-time service, I need to know *why* the packet failed. Is it congestion? Or is the physical link negotiation failing because the carrier is refarming frequencies?

I’ve started implementing aggressive heartbeat mechanisms that don’t just check for “up” or “down,” but measure the quality of the link. Here is a Python pattern I use to monitor latency jitter, which is usually the first sign that a client is about to drop off a high-speed band.

import time

import socket

import statistics

class NetworkHealthMonitor:

def __init__(self, target_host="8.8.8.8", port=53):

self.target = (target_host, port)

self.history = []

self.max_history = 20

def ping_probe(self):

# We use a simple TCP connect probe for application-layer latency

# This mimics actual traffic better than ICMP for our needs

start = time.perf_counter()

try:

sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

sock.settimeout(2.0)

sock.connect(self.target)

sock.close()

latency = (time.perf_counter() - start) * 1000

self._record(latency)

return latency

except socket.error:

self._record(None)

return None

def _record(self, latency):

self.history.append(latency)

if len(self.history) > self.max_history:

self.history.pop(0)

def analyze_jitter(self):

valid_pings = [x for x in self.history if x is not None]

if len(valid_pings) < 5:

return "INSUFFICIENT_DATA"

avg = statistics.mean(valid_pings)

stdev = statistics.stdev(valid_pings)

# If standard deviation is high relative to the mean, we have jitter

if stdev > (avg * 0.5):

return "UNSTABLE"

elif avg > 300:

return "HIGH_LATENCY"

return "STABLE"

monitor = NetworkHealthMonitor()

# Simulate a loop

for _ in range(10):

lat = monitor.ping_probe()

status = monitor.analyze_jitter()

print(f"Latency: {lat}ms | Status: {status}")

time.sleep(1)I prefer this approach because it operates at the Transport Layer. It gives me a realistic view of what my TCP/IP stack is experiencing. If the status flips to “UNSTABLE,” I immediately throttle my application’s bandwidth usage before the OS even realizes the connection is degrading.

IPv6 is No Longer Optional

Another friction point I run into constantly is the stubborn reliance on IPv4. With the expansion of 4G and the testing of 6G networks, carriers are using Carrier-Grade NAT (CGNAT) aggressively for IPv4, which wreaks havoc on P2P connections and VoIP. IPv6 is the native language of modern mobile infrastructure.

I recently debugged an issue where a Digital Nomad friend couldn’t connect to our VPN while working from a remote coastal town. The local ISP had upgraded their towers and put all IPv4 traffic through a heavily congested NAT, while IPv6 traffic was routed directly. Our VPN config was hardcoded to an IPv4 endpoint. The moment we enabled dual-stack support, the latency dropped by 60ms.

If you are doing Network Design in 2025, you must prioritize IPv6. Subnetting and CIDR calculations are different, sure, but the performance benefits on mobile networks are tangible. Stop treating IPv6 as a “nice to have.” It is the primary transport for the networks replacing the old 3G grids.

The Edge Computing Shift

As bandwidth increases, latency becomes the new bottleneck. We are seeing a massive push towards Edge Computing. This isn’t just marketing fluff; it changes how I write API calls. Instead of a centralized REST API in us-east-1, I’m deploying logic to edge nodes that sit closer to the user.

This introduces a synchronization problem. How do you keep data consistent when your user is hopping between edge nodes as they travel? I’ve moved away from strict consistency models for mobile apps and embraced eventual consistency using conflict-free replicated data types (CRDTs). It complicates the Protocol Implementation, but it ensures the app works even when the network is transitioning.

Here is a conceptual example of how I structure a resilient upload using a Python generator. This allows the upload to pause and resume across network changes, which is critical when a user moves from a dead zone back into 5G coverage.

import requests

import os

def resilient_upload(file_path, url, chunk_size=1024*1024):

file_size = os.path.getsize(file_path)

uploaded_bytes = 0

with open(file_path, 'rb') as f:

while uploaded_bytes < file_size:

# Check network status before attempting chunk

# (Assume check_network() is our custom health check)

if not check_network():

print("Network unstable, pausing upload...")

time.sleep(5)

continue

chunk = f.read(chunk_size)

if not chunk:

break

headers = {

'Content-Range': f'bytes {uploaded_bytes}-{uploaded_bytes + len(chunk) - 1}/{file_size}',

'Content-Type': 'application/octet-stream'

}

try:

response = requests.put(url, data=chunk, headers=headers, timeout=10)

if response.status_code in [200, 201, 308]:

uploaded_bytes += len(chunk)

print(f"Uploaded {uploaded_bytes}/{file_size} bytes")

else:

# Server rejected chunk, maybe token expired?

print(f"Upload failed: {response.status_code}")

break

except requests.exceptions.RequestException:

# Network failed during transfer

print("Connection lost during chunk, retrying...")

f.seek(uploaded_bytes) # Rewind to last success

time.sleep(2)

def check_network():

# Placeholder for actual connectivity check

return True This style of Network Programming is more verbose, but it saves user data. I use similar logic when dealing with Cloud Networking storage services. You cannot trust the OS to handle the buffer correctly when the physical interface switches from Wi-Fi to LTE.

Security at Speed

With faster networks comes faster attacks. Network Security is no longer just about Firewalls at the perimeter. The perimeter is on the device. I'm seeing more automated attacks targeting API endpoints that expose sensitive data. Since we are moving towards Microservices and Service Mesh architectures, every service-to-service communication needs to be authenticated.

I enforce mutual TLS (mTLS) wherever possible. It adds overhead, but with the CPU power in modern devices and the bandwidth of 5G, the latency penalty is negligible compared to the security gain. However, debugging mTLS issues is a nightmare if you don't know your way around openssl or Wireshark. Packet Analysis becomes a daily task. I often have to capture traffic on a mobile interface to see why a handshake failed during a cell tower handover.

A common issue I find is MTU size mismatches. New network equipment often supports Jumbo Frames, but intermediate legacy gear does not. If your HTTPS Protocol handshake packets are too large and the "Don't Fragment" bit is set, they get dropped silently. This looks like a timeout to the application. I always clamp my MSS (Maximum Segment Size) on VPN interfaces to avoid this specific headache.

The Human Element: Travel Tech and Remote Work

I do a fair bit of Travel Photography and work remotely, so I am my own best tester. I've tried uploading RAW images from a train in rural areas and from a cafe in a dense city center. The variance is wild. In the city, I might get interference on the 2.4GHz Wi-Fi band, while on the train, I'm dealing with Doppler shift affecting the LTE signal.

This experience taught me that Network Troubleshooting isn't just for the sysadmin. As a developer, I need to build tools into my app that help the user diagnose the issue. Instead of a generic "Connection Error," my apps now run a quick DNS Protocol check and a ping to the gateway. If DNS fails but the gateway answers, I tell the user "Internet is working, but DNS is down." This specificity reduces support tickets and helps the user understand it's likely their ISP, not my server.

Modernizing the Toolset

If you are still debugging networks with just ping and traceroute, you are falling behind. I rely heavily on Network Automation tools and Python libraries like Netmiko or Nornir when I'm managing infrastructure. For application-side debugging, I use browser developer tools to analyze the waterfall of API requests.

We also need to talk about Software-Defined Networking (SDN). In a modern cloud environment, the "switch" and "router" are just software abstractions. I configure Virtual Private Clouds (VPCs) and Load Balancing rules via Terraform, not via a CLI console cable. This means Network Administration is now effectively code. If you make a typo in your routing table definition, you can isolate an entire subnet.

I recommend getting comfortable with GraphQL for your data fetching. Unlike REST, where you might make five different calls to get user data, posts, and comments (risking failure on each one), GraphQL lets you fetch everything in a single request. On a flaky mobile network, minimizing round-trips is the single best performance optimization you can make. It reduces the window of opportunity for the connection to drop.

The transition we are seeing right now—where 3G fades out and 6G concepts begin to surface—is messy. It leaves gaps in coverage and creates edge cases that we haven't had to deal with for years. But it also forces us to write better, more resilient software. If you treat the network as a hostile environment in your code, your users will have a smooth experience even when the infrastructure is falling apart around them.