I stopped trusting my ISP-provided router about three years ago, but the events of 2025 have really cemented that paranoia. We spend so much time obsessing over endpoint security—hardening our MacBooks, locking down Windows 11, and scrutinizing iOS permissions—that we completely ignore the black box blinking in the closet. That device is the gateway to everything we own, and frankly, the current state of consumer network devices is a disaster waiting to happen.

I’m writing this because I’m tired of seeing colleagues get compromised not because they clicked a phishing link, but because a packet hit their WAN interface and their router didn’t know how to handle it. We are seeing a massive uptick in mercenary spyware and sophisticated tools that exploit zero-click vulnerabilities. These aren’t the “download this PDF” attacks of the last decade. These are network-based attacks where the user does absolutely nothing, and the adversary gains a foothold.

If you are a Network Engineer, a DevOps Networking pro, or just someone who cares about their digital privacy, you need to stop treating your router and switches as “set and forget” appliances. Here is how I approach hardening network infrastructure against these invisible threats.

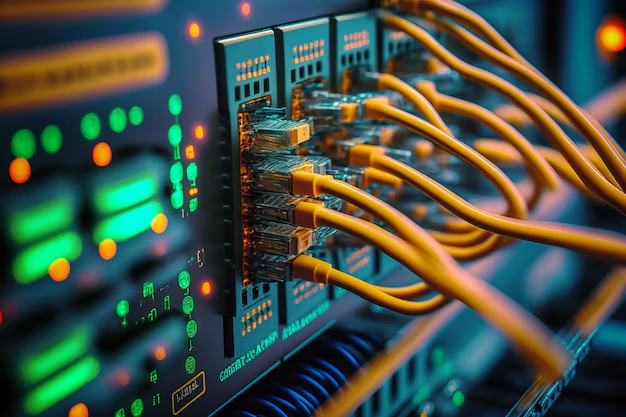

The Hardware Layer: Why Your Router is the Weakest Link

The fundamental problem I see is that most network devices run proprietary firmware that rarely gets patched. When a zero-day hits an operating system like Android or iOS, the vendor usually pushes a patch within days. When a vulnerability is found in the TCP/IP stack of a budget router, you might wait six months for a firmware update, if you get one at all.

I treat every network device as potentially hostile. The attack surface isn’t just the management interface; it’s the packet processing logic itself. If an attacker can send a malformed IPv6 packet that causes a buffer overflow in the router’s memory, they can execute code with root privileges on that device. Once they own the router, they can perform Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks, strip SSL where HSTS isn’t enforced, or redirect your DNS requests.

To combat this, I’ve moved entirely to Software-Defined Networking (SDN) and open-source firmware where possible. I want visibility. If I can’t see the logs, I don’t use the device. For my home lab and remote work setups, I use hardware that supports OpenWrt or pfSense. This allows me to update the underlying OS independently of the hardware vendor.

Network Segmentation: The “Blast Radius” Strategy

I assume that eventually, something on my network will get hit. It might be a smart bulb, a printer, or an older tablet. The goal isn’t just prevention; it’s containment. I use strict Network Segmentation via VLANs (Virtual Local Area Networks) to ensure that a compromised device can’t talk to my critical infrastructure.

My Network Architecture is designed around three core zones:

- Trusted Zone: My workstations and servers.

- IoT/Untrusted Zone: Smart TVs, cameras, and “smart” appliances. These devices are blocked from accessing the internet unless strictly necessary, and they absolutely cannot talk to the Trusted Zone.

- Guest Zone: For visitors. Client isolation is enabled, meaning devices in this zone can’t even talk to each other.

Configuring this requires a router and switches that support 802.1Q tagging. I use Python to audit my switch configurations because clicking through a GUI is error-prone. Here is a script I use with the netmiko library to verify VLAN assignments on my Cisco switches. It ensures that no port is accidentally left in the default VLAN 1, which is a common security oversight.

import netmiko

from getpass import getpass

def audit_switch_vlans(ip, username, password):

device = {

'device_type': 'cisco_ios',

'ip': ip,

'username': username,

'password': password,

}

try:

connection = netmiko.ConnectHandler(**device)

print(f"Connected to {ip}")

# Get interface status to find access ports

output = connection.send_command("show interfaces status")

lines = output.split('\n')

vlan_1_ports = []

for line in lines:

# parsing logic varies by switch model, this is a simplified example

if "connected" in line and " 1 " in line: # Checks for VLAN 1

parts = line.split()

vlan_1_ports.append(parts[0])

if vlan_1_ports:

print(f"WARNING: The following connected ports are on Default VLAN 1: {vlan_1_ports}")

print("Action: Move these ports to a specific data or guest VLAN immediately.")

else:

print("Audit Passed: No connected ports found on VLAN 1.")

connection.disconnect()

except Exception as e:

print(f"Failed to connect: {e}")

# In a real deployment, I loop this through my inventory file

# audit_switch_vlans('192.168.10.2', 'admin', getpass())I run this script weekly. It’s a simple check, but it prevents “configuration drift” where I plug something in for testing and forget to isolate it.

The VPN Layer: Encryption as the Last Line of Defense

When discussing protection against network-based attacks, we have to talk about VPNs. But I’m not talking about buying a commercial VPN service to watch Netflix in another country. I’m talking about using a VPN to secure your traffic against the local network infrastructure itself.

If I am traveling—Digital Nomad style—and using hotel Wi-Fi, I assume the hotel router is compromised. It’s likely running firmware from 2019 and is infested with malware. To mitigate this, I tunnel 100% of my traffic back to my trusted home network or a cloud VPS using WireGuard.

WireGuard is superior to OpenVPN for this because it’s lighter, faster, and handles roaming (switching from Wi-Fi to 5G) much better. By encapsulating my traffic, even if the local router is malicious and trying to inject code or analyze my packets, all they see is encrypted UDP garbage.

Here is the client configuration I use on my travel router (a small GL.iNet device I carry everywhere). This forces all traffic through the tunnel (0.0.0.0/0), effectively bypassing the local network’s prying eyes.

[Interface]

PrivateKey = <MY_CLIENT_PRIVATE_KEY>

Address = 10.100.0.2/24

DNS = 10.100.0.1

# MTU tuning is critical for some hotel networks that block large packets

MTU = 1320

[Peer]

PublicKey = <SERVER_PUBLIC_KEY>

# Route ALL traffic through the tunnel

AllowedIPs = 0.0.0.0/0, ::/0

Endpoint = my.secure-server.com:51820

# Keep the connection alive through NAT traversals

PersistentKeepalive = 25I specifically lower the MTU (Maximum Transmission Unit) to 1320. I found that many poorly configured networks drop fragmented packets, which causes connection hangs. Lowering the MTU ensures my encrypted packets fit inside standard frames without fragmentation.

Monitoring: Detecting the Invisible

You cannot stop what you cannot see. Most consumer routers give you zero insight into what is actually leaving your network. If a smart thermometer starts sending 5GB of data to an IP address in a foreign country, a standard router won’t alert you.

I use a combination of DNS logging and Flow analysis. For DNS, I point everything to a local resolver (like Pi-hole or AdGuard Home) or a cloud provider like NextDNS that offers analytics. This kills two birds with one stone: it blocks ad trackers and prevents malware from phoning home to Command and Control (C2) servers.

However, sophisticated spyware might bypass DNS and use hardcoded IP addresses. This is where packet analysis comes in. I don’t sit and stare at Wireshark all day, but I do run a collector that looks for anomalies. One specific anomaly I watch for is ARP Spoofing. This is a technique where an attacker (or a compromised device) lies to the network, saying “I am the router,” to intercept traffic.

I wrote a quick Python tool using raw sockets to listen for ARP changes. It’s rudimentary, but it alerts me if a MAC address for the gateway suddenly changes—a huge red flag.

import socket

import struct

import binascii

def get_mac_format(mac_raw):

# Convert binary MAC to human readable string

mac_str = map('{:02x}'.format, mac_raw)

return ':'.join(mac_str).upper()

def monitor_arp():

# Create a raw socket to listen for ARP packets

# Note: Requires root/admin privileges

try:

raw_socket = socket.socket(socket.AF_PACKET, socket.SOCK_RAW, socket.htons(0x0003))

except AttributeError:

print("This script requires Linux/Unix raw sockets.")

return

print("Listening for ARP packets...")

known_gateway_mac = "AA:BB:CC:DD:EE:FF" # My Router's Real MAC

gateway_ip = "192.168.1.1"

while True:

packet = raw_socket.recvfrom(2048)

ethernet_header = packet[0][0:14]

eth_header = struct.unpack("!6s6s2s", ethernet_header)

ether_type = binascii.hexlify(eth_header[2]).decode()

# Check if it's an ARP packet (0806)

if ether_type == '0806':

arp_header = packet[0][14:42]

arp_detailed = struct.unpack("2s2s1s1s2s6s4s6s4s", arp_header)

sender_mac = get_mac_format(arp_detailed[5])

sender_ip = socket.inet_ntoa(arp_detailed[6])

# If someone claims to be the gateway IP but has the WRONG MAC

if sender_ip == gateway_ip and sender_mac != known_gateway_mac:

print(f"ALERT: ARP Spoofing Detected! {sender_ip} is being claimed by {sender_mac}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

# monitor_arp()

passRunning tools like this on a Raspberry Pi connected to a mirror port on my switch gives me peace of mind. If the network changes, I know about it.

The Role of Updates and End-of-Life Gear

We need to be ruthless about hardware lifecycles. I see people running routers that went End-of-Life (EOL) in 2020. That is negligent. If a vendor stops releasing security patches for a device, it belongs in the e-waste recycling bin, not on your network edge.

With the current threat level, “it still works” is not a valid reason to keep hardware. Zero-click exploits often rely on unpatched vulnerabilities in older versions of OpenSSL or the Linux kernel embedded in these devices. I maintain a spreadsheet of my hardware and check the vendor support status quarterly. If a device loses support, I replace it immediately. It’s a cost of doing business in a connected world.

Disabling Convenience Features

To harden a network, you have to sacrifice some convenience. The first thing I disable on any router is UPnP (Universal Plug and Play). UPnP is a protocol that allows applications inside your network to automatically open ports on your firewall. It is a massive security hole. Malware uses UPnP to turn your router into a proxy server for illegal activities.

I also disable WPS (Wi-Fi Protected Setup) and remote management interfaces. If I need to manage my network remotely, I VPN in first, then access the local management IP. Exposing a web login page to the open internet is asking for a brute-force attack or an exploit of the web server daemon.

Conclusion: A Shift in Mindset

The reality of 2025 is that we can no longer trust the network to be a dumb pipe. It is an active battlefield. Mercenary spyware vendors are actively hunting for entry points that bypass the operating system entirely. By hardening the network layer—through segmentation, encryption, and rigorous monitoring—we make their job significantly harder.

I encourage you to audit your own setup this week. Log into your router, check the firmware date, and look at your firewall rules. If you find yourself thinking, “I don’t know what that rule does,” delete it. Paranoia is just good practice when the hardware itself is under attack.