The Unseen Engine: Understanding IPv4 in Modern Computer Networking

Have you ever typed an address like 192.168.1.1 to access your router’s settings or configured a DNS server using 8.8.8.8? These familiar strings of numbers are IPv4 addresses, the fundamental building blocks of the internet as we know it. For over four decades, Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4) has been the workhorse protocol responsible for identifying devices on a network and routing traffic between them. It operates at the Network Layer of the OSI model, providing the logical addressing system that underpins nearly all digital communication.

While the world is slowly transitioning to its successor, IPv6, a deep understanding of IPv4 remains absolutely critical for anyone in technology. From network engineers and system administrators to DevOps professionals and software developers, grasping the principles of IPv4 is essential for effective network design, troubleshooting, and security. This article provides a comprehensive exploration of IPv4, from its core structure and subnetting principles to its role in modern network programming and cloud networking, offering practical examples and insights along the way.

The Anatomy of an IPv4 Address

At its core, IPv4 is a protocol that provides a unique numerical identifier for every device connected to a network. This allows data packets to be sent from a source and correctly delivered to a destination, whether it’s across the room or across the globe. Understanding this addressing scheme is the first step to mastering network communication.

The 32-Bit Structure: Dotted-Decimal Notation

An IPv4 address is a 32-bit binary number. To make it human-readable, this 32-bit number is divided into four 8-bit segments called octets. Each octet is then converted to its decimal equivalent and separated by a dot. This is known as “dotted-decimal notation.” For example, the binary address:

11000000.10101000.00000001.00000001

…translates to the more familiar decimal address:

192.168.1.1

Since each octet is 8 bits, its decimal value can range from 0 (00000000) to 255 (11111111). This 32-bit structure provides a total of 2³² (approximately 4.3 billion) possible unique addresses—a number that seemed vast at its inception but has since proven insufficient for the explosive growth of the internet.

From Classful Addressing to CIDR

Initially, IPv4 addresses were divided into “classes” (A, B, C, D, E) to allocate address blocks of different sizes. For instance, Class A networks had a small number of networks but could support millions of hosts, while Class C networks were numerous but supported only 254 hosts each. This system was rigid and led to inefficient address allocation.

To solve this, Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR) was introduced. CIDR notation appends a slash and a number to the IP address (e.g., 192.168.1.0/24). This number, the prefix, represents how many bits are used for the network portion of the address. A /24 prefix means the first 24 bits identify the network, leaving the remaining 8 bits for host addresses. This flexible system allows for precise allocation of IP address blocks, a practice known as subnetting.

We can use Python’s built-in ipaddress module to easily parse and validate IPv4 addresses and networks defined with CIDR notation. This is incredibly useful for network automation and scripting tasks.

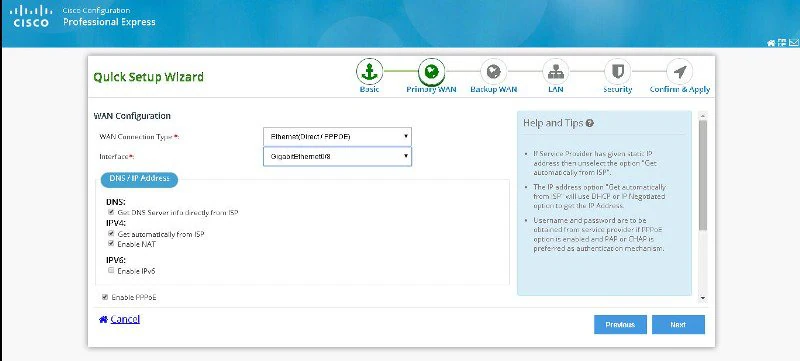

router configuration page 192.168.1.1 – How to Log In to the 192.168.1.1 Router Management Page | IP …

import ipaddress

def analyze_ipv4_network(network_str):

"""

Analyzes an IPv4 network address in CIDR notation.

"""

try:

# Create a network object from the CIDR string

network = ipaddress.ip_network(network_str, strict=False)

print(f"Analyzing Network: {network_str}")

print(f" - Is a valid network: True")

print(f" - Network Address: {network.network_address}")

print(f" - Broadcast Address: {network.broadcast_address}")

print(f" - Netmask: {network.netmask}")

print(f" - Number of available hosts: {network.num_addresses - 2}") # Excludes network and broadcast

print(f" - Is private network: {network.is_private}")

# List the first 5 usable IP addresses

print(" - First 5 usable host addresses:")

count = 0

for ip in network.hosts():

if count < 5:

print(f" - {ip}")

count += 1

else:

break

except ValueError as e:

print(f"Error analyzing '{network_str}': {e}")

# --- Example Usage ---

# A common private network used in homes and small offices

analyze_ipv4_network("192.168.1.0/24")

print("\n" + "-"*20 + "\n")

# A public IP block

analyze_ipv4_network("8.8.8.0/24")IPv4 in Action: Subnetting, Routing, and Special Addresses

With the basic structure defined, we can explore how IPv4 functions in a real-world network. This involves dividing networks logically (subnetting), directing traffic between them (routing), and understanding the roles of special address ranges.

Subnetting: Dividing Networks for Efficiency and Security

Subnetting is the process of taking a large network block and breaking it down into smaller, more manageable sub-networks, or “subnets.” This practice is fundamental to modern network design. It helps reduce network congestion by isolating broadcast traffic within a subnet, improves security by allowing administrators to apply access policies between subnets, and simplifies network administration.

A subnet mask is a 32-bit number that mirrors the format of an IPv4 address. It uses a sequence of `1`s followed by `0`s to define which part of an IP address is the network portion and which is the host portion. For a /24 network, the subnet mask is 255.255.255.0, which is 24 ones in binary.

How Routing Works: Getting Packets to Their Destination

Routing is the core function of the Network Layer. When a device wants to send a packet, it first checks if the destination IP is on the same local network (subnet). If it is, the packet is sent directly. If not, the packet is sent to the network’s default gateway—typically a router. The router then examines the destination IP address, consults its routing table, and forwards the packet to the next “hop” on the path toward the final destination. This process repeats across multiple routers until the packet arrives.

You can observe this process using common network commands. The `ping` command tests reachability, while `traceroute` (or `tracert` on Windows) shows the step-by-step path a packet takes to its destination.

# 1. Check your local IPv4 configuration

# On Linux/macOS

ip addr show eth0

# On Windows

ipconfig

# 2. Test connectivity to a known public server (Google's DNS)

# The -c 4 flag sends 4 packets.

ping -c 4 8.8.8.8

# 3. Trace the route your packets take to reach the server

# On Linux/macOS

traceroute 8.8.8.8

# On Windows

tracert 8.8.8.8Special Address Ranges: Private vs. Public IPs

Not all 4.3 billion IPv4 addresses are routable on the public internet. The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) has reserved specific blocks for use in private networks (e.g., your home WiFi, corporate LANs). These are:

- 10.0.0.0/8 (10.0.0.0 to 10.255.255.255)

- 172.16.0.0/12 (172.16.0.0 to 172.31.255.255)

- 192.168.0.0/16 (192.168.0.0 to 192.168.255.255)

These private addresses are not unique globally and can be reused by anyone. To communicate with the public internet, devices with private IPs must go through a router that performs Network Address Translation (NAT).

Advanced Concepts and Network Programming

Beyond addressing and routing, IPv4 involves a detailed packet structure and serves as the foundation for higher-level protocols and network programming. Understanding these aspects is crucial for network security, performance analysis, and software development.

The IPv4 Packet Header: A Closer Look

Every IPv4 packet contains a header with crucial information for routing and processing. Key fields include:

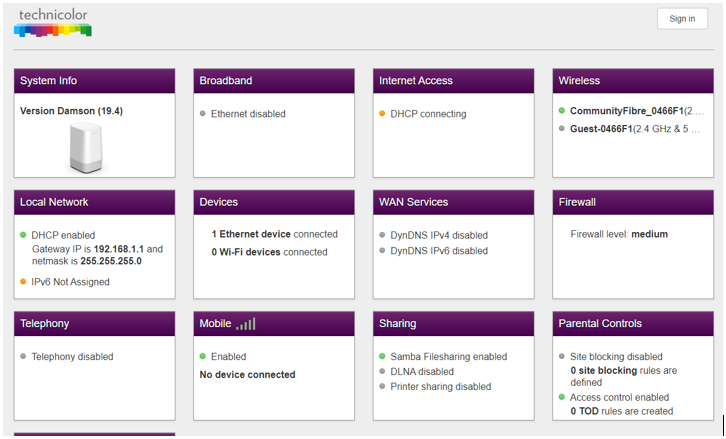

router configuration page 192.168.1.1 – How do I set up my Technicolor WiFi 6 router for my 5 Gbps Full …

- Version: Always 4 for IPv4.

- Time to Live (TTL): A counter that is decremented by each router; if it reaches zero, the packet is discarded to prevent infinite routing loops.

- Protocol: Indicates the encapsulated protocol in the data portion (e.g., 6 for TCP, 17 for UDP).

- Source Address: The 32-bit IPv4 address of the sender.

- Destination Address: The 32-bit IPv4 address of the recipient.

Tools like Wireshark allow for deep packet analysis, letting you inspect these headers in real-time. This is an indispensable skill for network troubleshooting and security analysis, helping to diagnose issues related to firewalls, routing, or application performance.

Network Address Translation (NAT)

NAT is a technique used by routers to allow multiple devices in a private network to share a single public IPv4 address. When a device sends a packet to the internet, the router replaces the private source IP with its own public IP. It keeps a record of this translation so that when the response comes back, it can forward it to the correct private device. NAT has been instrumental in extending the life of IPv4 by conserving the limited supply of public addresses.

Socket Programming with IPv4

Developers interact with IPv4 through APIs, most commonly the Sockets API. Sockets provide the programming interface for creating network connections. When you build a web service or a client application, you are using sockets to communicate over TCP/IP. The DNS protocol is used to resolve a human-friendly hostname (like `google.com`) into its corresponding IPv4 address before a socket connection can be established.

Here’s a simple Python example using the socket library to perform a DNS lookup and then attempt to connect to a web server on port 80 (HTTP).

import socket

def connect_to_server(hostname, port):

"""

Resolves a hostname to an IPv4 address and attempts to connect.

"""

print(f"Attempting to connect to {hostname} on port {port}...")

try:

# Step 1: Resolve the hostname to an IPv4 address (DNS lookup)

ipv4_address = socket.gethostbyname(hostname)

print(f" - Resolved '{hostname}' to IPv4 address: {ipv4_address}")

# Step 2: Create a socket object for an IPv4 TCP connection

# AF_INET specifies the IPv4 address family.

# SOCK_STREAM specifies that this is a TCP socket.

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

# Set a timeout to avoid waiting indefinitely

s.settimeout(5)

# Step 3: Connect to the server using its IP and port

s.connect((ipv4_address, port))

print(f" - Successfully connected to {ipv4_address}:{port}")

except socket.gaierror:

print(f" - Error: Could not resolve hostname '{hostname}'. Check DNS settings.")

except socket.error as e:

print(f" - Error: Could not connect. Reason: {e}")

# --- Example Usage ---

connect_to_server("example.com", 80) # Standard HTTP port

print("\n" + "-"*20 + "\n")

connect_to_server("invalid-hostname-that-does-not-exist.xyz", 80)Best Practices, Troubleshooting, and the Future

Mastering IPv4 involves not only understanding its mechanics but also applying best practices for its management, security, and eventual migration. In today’s complex environments, from on-premise data centers to cloud networking, these skills are more valuable than ever.

Network Security Considerations

router configuration page 192.168.1.1 – How to Access 192.168.1.1 Login Page on Mobile? What is the …

Because IPv4 operates at the network layer, it is a primary focus for security measures. Firewalls are network devices or software that filter traffic based on rules defined by source/destination IP addresses, ports, and protocols. Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) use tunneling protocols to encapsulate IPv4 packets within other packets, creating a secure, encrypted channel over an untrusted network like the public internet.

The Inevitable Transition: IPv4 vs. IPv6

IPv4 address exhaustion is a real problem. Its successor, IPv6, uses a 128-bit address, providing a virtually limitless number of unique addresses. While the global adoption of IPv6 is ongoing, it is a slow process. For the foreseeable future, networks will operate in a “dual-stack” mode, supporting both IPv4 and IPv6 simultaneously. Therefore, network engineers and administrators must be proficient in both protocols.

IPv4 in Modern Architectures: Cloud and SDN

In modern IT, IPv4 is managed at scale through automation. In Cloud Networking (e.g., AWS VPC, Azure VNet), IP addressing and subnetting are defined programmatically. Software-Defined Networking (SDN) abstracts the network control plane from the physical hardware, allowing for centralized management and automation of network configurations, including IP address assignments and routing policies, often via REST APIs. This shift towards Network Automation makes scripting skills, like the Python examples shown earlier, essential for the modern network professional.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of IPv4

IPv4 is much more than a string of four numbers; it is the foundational addressing system that has enabled the internet to grow and connect the world. From its 32-bit structure and the flexibility of CIDR to its critical role in routing and network security, IPv4 concepts are woven into the fabric of every network. While the future belongs to IPv6, the principles, challenges, and solutions developed for IPv4—like subnetting, NAT, and packet analysis—remain highly relevant.

For anyone involved in technology, a solid grasp of IPv4 is non-negotiable. It is the key to effective network troubleshooting, robust network design, and secure system administration. As you continue your journey, dive deeper into tools like Wireshark, practice subnetting calculations until they become second nature, and begin exploring the parallel world of IPv6. By mastering the protocol that built the internet, you will be well-equipped to manage and innovate on the networks of tomorrow.