In the world of Computer Networking, few concepts are as fundamental yet as frequently underestimated as network addressing. For a small, single-site network, assigning IP addresses might seem like a trivial task. However, as an organization grows—adding new sites, deploying services in the cloud, and connecting remote workers via VPN—that simple task rapidly transforms into a complex puzzle. Without a strategic and well-documented addressing plan, networks become fragile, difficult to troubleshoot, and a significant bottleneck to business agility. This is the silent challenge that trips up many network administrators and even seasoned DevOps professionals.

A solid understanding of network addressing is the bedrock of robust Network Architecture. It’s about more than just avoiding IP conflicts; it’s about designing a logical, segmented, and secure framework that can scale with demand. This article provides a comprehensive deep dive into the principles, best practices, and modern automation techniques for network addressing. We’ll move from the core concepts of IPv4 and subnetting to advanced strategies like IP Address Management (IPAM) and API-driven network automation, providing practical code examples to bridge theory and real-world application.

The Foundations of IP Addressing and Subnetting

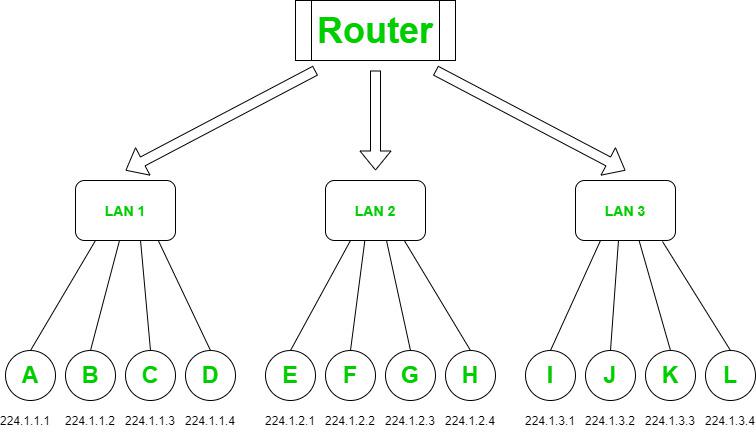

At its core, network addressing is the system that provides unique identifiers to devices on a network, enabling them to communicate. This is governed by the Internet Protocol (IP), which sits at the Network Layer of the OSI Model. Understanding how to partition and manage these addresses is the first step toward effective Network Design.

IPv4, Subnet Masks, and CIDR Notation

The most widely used protocol today is still IPv4, which uses a 32-bit address, commonly written as four octets (e.g., 192.168.1.10). An IP address has two parts: the network portion and the host portion. The subnet mask is what tells a device which part is which. For example, a subnet mask of 255.255.255.0 indicates that the first three octets identify the network, and the last octet identifies the host.

This system was simplified by Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR), which appends a slash and a number representing the count of leading network bits. For example, 192.168.1.0/24 is equivalent to the network 192.168.1.0 with a subnet mask of 255.255.255.0. CIDR provides immense flexibility, allowing network engineers to create networks of virtually any size, a practice known as subnetting.

Subnetting is crucial for several reasons:

- Performance: It reduces the size of broadcast domains, minimizing unnecessary traffic and improving Network Performance.

- Security: It allows for the logical segmentation of a network. You can place servers in one subnet, user workstations in another, and guest Wi-Fi devices in a third, then use Firewalls to control traffic between them.

- Organization: It creates a logical, hierarchical structure that simplifies Network Troubleshooting and management.

Let’s use Python’s built-in ipaddress library to explore a CIDR block. This is a common task in Network Automation scripts.

import ipaddress

def analyze_subnet(cidr_block):

"""

Analyzes a given CIDR block and prints its key properties.

"""

try:

net = ipaddress.ip_network(cidr_block, strict=False)

print(f"Analyzing Subnet: {net.with_prefixlen}")

print(f"------------------------------------")

print(f"Network Address: {net.network_address}")

print(f"Broadcast Address: {net.broadcast_address}")

print(f"Subnet Mask: {net.netmask}")

print(f"Total Hosts: {net.num_addresses}")

# Usable hosts are total addresses minus network and broadcast addresses

if net.prefixlen < 31:

print(f"Usable Hosts: {net.num_addresses - 2}")

else:

print(f"Usable Hosts: {net.num_addresses} (Point-to-Point)")

# Get first and last usable IP

if net.prefixlen < 31:

hosts = list(net.hosts())

print(f"Usable Host Range: {hosts[0]} - {hosts[-1]}")

except ValueError as e:

print(f"Error: Invalid CIDR block provided. {e}")

# --- Example Usage ---

analyze_subnet("192.168.10.0/24")

print("\n")

analyze_subnet("10.50.0.0/22")Designing a Scalable Addressing Scheme

A common mistake in Network Administration is allocating address space with only immediate needs in mind. A department that needs 20 IPs gets a /27 subnet (30 usable hosts), leaving no room for growth. A scalable design anticipates future needs and uses techniques like Variable Length Subnet Masking (VLSM) to allocate addresses efficiently.

Planning for Growth with VLSM

Variable Length Subnet Masking (VLSM) is a technique where you subnet a network into smaller subnets of different sizes. This is incredibly efficient. Instead of breaking a large block into many equally sized chunks (many of which might be too large for their purpose), you can create subnets tailored to specific needs. For example, a large /16 block can be carved up to provide:

- A few

/23subnets for large user departments. - Several

/26subnets for server farms. - Numerous

/30subnets for point-to-point links between Routers.

The key is to start with the largest requirements first and allocate subnets contiguously from your main address block. This keeps the routing table clean and the overall Network Architecture logical.

Let’s write a Python script to demonstrate a simple VLSM calculation. This function will take a parent network and a list of required host counts, then allocate the necessary subnets.

import ipaddress

def calculate_vlsm(parent_cidr, department_requirements):

"""

Calculates VLSM subnets based on a list of host requirements.

Args:

parent_cidr (str): The main network block (e.g., '10.10.0.0/16').

department_requirements (dict): A dict of {dept_name: required_hosts}.

"""

try:

parent_network = ipaddress.ip_network(parent_cidr)

print(f"Parent Network: {parent_network}\n")

# Sort departments by required hosts, descending

sorted_depts = sorted(

department_requirements.items(),

key=lambda item: item[1],

reverse=True

)

allocated_subnets = {}

available_networks = [parent_network]

for dept_name, hosts_needed in sorted_depts:

# We need hosts_needed + 2 addresses (network and broadcast)

required_size = hosts_needed + 2

# Calculate the required prefix length

# 32 - prefixlen must be >= log2(required_size)

prefixlen = 32 - required_size.bit_length()

# Find a suitable available network to subnet from

allocated = False

for i, net in enumerate(available_networks):

if net.prefixlen <= prefixlen:

# Found a network large enough to accommodate the request

new_subnet = next(net.subnets(new_prefix=prefixlen))

allocated_subnets[dept_name] = new_subnet

# Update the list of available networks

remaining = list(net.address_exclude(new_subnet))

available_networks.pop(i)

available_networks.extend(remaining)

available_networks.sort() # Keep it tidy

allocated = True

break

if not allocated:

print(f"Could not allocate subnet for {dept_name} requiring {hosts_needed} hosts.")

return allocated_subnets

except ValueError as e:

print(f"Error: {e}")

return None

# --- Example Usage ---

# A company needs to structure its internal network

requirements = {

"Engineering": 120,

"Sales": 55,

"Servers": 28,

"WAN_Link_1": 2,

"WAN_Link_2": 2

}

allocations = calculate_vlsm("172.16.0.0/20", requirements)

if allocations:

print("--- VLSM Allocations ---")

for dept, subnet in allocations.items():

print(f"{dept:<15}: {str(subnet):<18} ({subnet.num_addresses - 2} usable hosts)")

Modern IP Address Management and Automation

As networks scale, managing addressing via spreadsheets becomes untenable. It’s prone to errors, lacks version control, and doesn’t integrate with other systems. This is where IP Address Management (IPAM) platforms come in. Tools like NetBox, Infoblox, or SolarWinds IPAM provide a centralized, “single source of truth” for your entire network.

IPAM as a Foundation for Network Automation

Modern IPAMs are more than just databases; they are powerful platforms with robust Network APIs (typically REST API). This is a game-changer for DevOps Networking. Instead of manually picking an IP address from a spreadsheet and then manually configuring a device, you can automate the entire workflow:

- An automation script (e.g., Ansible, Python) needs to provision a new virtual machine or a switch interface.

- The script makes an API call to the IPAM, requesting the next available IP address from a specific subnet (e.g., “Data Center Server Subnet”).

- The IPAM reserves the IP, marks it as active, and returns it to the script.

- The script then uses that IP to configure the device or VM.

This process is fast, error-free, and fully documented. It’s a cornerstone of modern, agile Network Administration and is essential for managing complex environments like Cloud Networking or large-scale data centers.

Below is a Python example simulating a request to a hypothetical IPAM’s REST API to get the next available IP address. This demonstrates how Network Programming connects with IPAM systems.

import requests

import json

# --- Configuration for a hypothetical IPAM ---

IPAM_URL = "https://ipam.example.com/api"

API_TOKEN = "your_secret_api_token_here"

SUBNET_ID = "101" # The internal ID of the subnet we want an IP from

def get_next_available_ip(subnet_id):

"""

Requests the next available IP address from a hypothetical IPAM via REST API.

"""

headers = {

"Authorization": f"Token {API_TOKEN}",

"Content-Type": "application/json",

"Accept": "application/json"

}

# The endpoint to get the next available IP is often a POST request

# to a specific sub-resource of the subnet.

api_endpoint = f"{IPAM_URL}/subnets/{subnet_id}/available-ips/"

print(f"Requesting next available IP from subnet ID {subnet_id}...")

try:

# We POST to this endpoint to create a new IP address allocation

response = requests.post(api_endpoint, headers=headers, timeout=10)

# Check for successful response

response.raise_for_status()

ip_data = response.json()

ip_address = ip_data.get("address") # e.g., "10.20.30.5/24"

if ip_address:

print(f"Successfully allocated IP: {ip_address}")

return ip_address

else:

print("Error: API response did not contain an address.")

return None

except requests.exceptions.HTTPError as e:

print(f"HTTP Error: {e.response.status_code} - {e.response.text}")

return None

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e:

print(f"Request failed: {e}")

return None

# --- Example Usage ---

# In a real script, this IP would then be used in an Ansible/Netmiko task

new_ip = get_next_available_ip(SUBNET_ID)

if new_ip:

print(f"\nNext step: Use '{new_ip}' to configure a new server or network device.")

Best Practices and Common Pitfalls

A well-designed addressing scheme is supported by strong operational practices. Ignoring them can undermine even the most technically sound plan. Here are some critical best practices for every Network Engineer to follow.

Documentation and Standardization

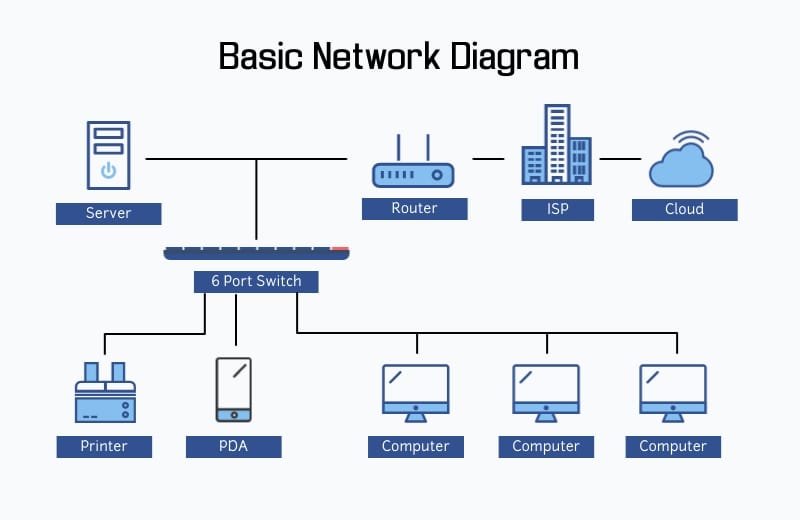

Document Everything: A network diagram is indispensable. It should clearly show sites, Routers, Switches, VLANs, and the subnets assigned to each. This documentation must be a living document, updated as part of any network change. This is the only way to keep the addressing scheme straight as the network grows.

Standardize Allocation: Create a simple, predictable pattern for assigning addresses within a subnet. For example:

.1: Primary gateway (Virtual Router Redundancy Protocol – VRRP/HSRP VIP)..2and.3: Physical router interfaces..254: Management IP for a switch or other infrastructure..10 - .50: Reserved for infrastructure like printers and servers.

This consistency dramatically speeds up Network Troubleshooting.

Security and Segmentation

Your addressing scheme is a powerful Network Security tool. By segmenting the network into different subnets (and corresponding VLANs), you create logical boundaries. You can then place a firewall between these subnets to enforce access control policies. For instance, a guest Wi-Fi subnet should never be able to directly access the corporate server subnet. This segmentation contains threats and reduces the attack surface.

Avoiding Address Overlap

One of the most common and disruptive problems is IP address overlap. This often happens during company mergers or when configuring a site-to-site VPN. If both networks use the popular 192.168.1.0/24 range, routing becomes impossible. Proactive planning is the only cure. Use less common private address ranges (e.g., from the 172.16.0.0/12 or 10.0.0.0/8 blocks) for your internal network. When establishing a VPN with a partner, always communicate and agree on non-overlapping address spaces beforehand.

Conclusion: Addressing as a Strategic Asset

Network addressing is far more than an administrative chore; it is a strategic element of Network Design that directly impacts performance, security, and scalability. Moving from a reactive, manual approach to a proactive, automated one is essential for any modern technology organization. By mastering the fundamentals of subnetting and CIDR, adopting a forward-looking design with VLSM, and leveraging the power of IPAM and Network Automation, you transform your network’s addressing scheme from a potential liability into a robust and agile asset.

The key takeaways are clear: plan for growth, document meticulously, standardize your conventions, and embrace automation. As your next step, explore an open-source IPAM solution like NetBox to see how a “single source of truth” can revolutionize your workflow. From there, begin integrating it with simple Python or Ansible scripts to automate the tedious tasks, freeing you to focus on higher-level architectural challenges.