In the rapidly evolving landscape of Cloud Networking and modern infrastructure, the physical constraints of traditional hardware have given way to the agility of software. Network Virtualization has emerged not just as a convenience, but as a fundamental necessity for scaling applications, managing Microservices, and orchestrating massive clusters via tools like Kubernetes. For the modern Network Engineer and DevOps Networking professional, understanding the intricate layers of virtualized connectivity is as critical as understanding TCP/IP itself.

Gone are the days when Network Architecture was defined solely by physical cabling and hardware appliances. Today, Software-Defined Networking (SDN) allows us to decouple the control plane from the data plane, enabling programmable, automated, and scalable networks. This article provides a comprehensive technical exploration of network virtualization, focusing on protocols like VXLAN, the mechanics of Linux networking, and the implementation of overlay networks that power the internet’s most robust systems.

Core Concepts: From VLANs to Overlay Networks

To understand where we are, we must look at the limitations of the past. Traditional Ethernet environments relied heavily on VLANs (Virtual Local Area Networks) to segment traffic. However, VLANs are limited to a 12-bit ID, capping the number of segments at 4096. In the era of multi-tenant cloud environments and massive Service Mesh deployments, this is insufficient.

The OSI Model and Encapsulation

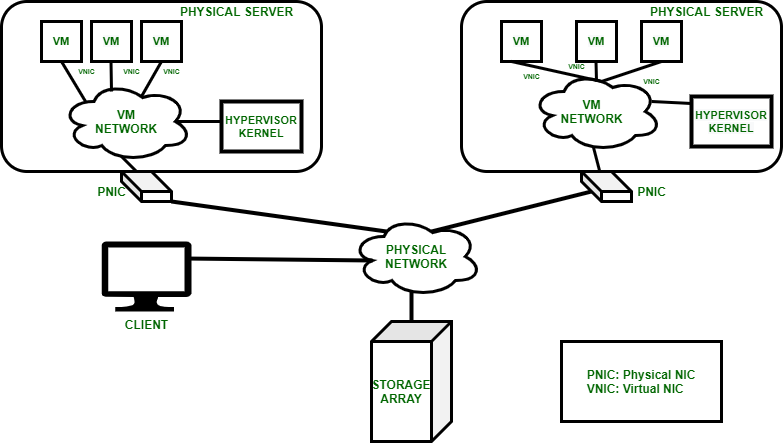

Network virtualization often operates by creating an “overlay” network on top of a physical “underlay” network. This relies heavily on the principles of the OSI Model, specifically manipulating the Network Layer (Layer 3) and Data Link Layer (Layer 2). The most prominent technology driving this shift is VXLAN (Virtual Extensible LAN).

VXLAN encapsulates Layer 2 Ethernet frames within Layer 3 UDP packets. This allows you to span a Layer 2 network across a Layer 3 infrastructure, effectively tunneling traffic across routers and the internet. This encapsulation is vital for Cloud Computing, enabling virtual machines or containers to communicate as if they were on the same physical switch, regardless of their actual geographic location—a concept even a Digital Nomad relying on VPN technology would appreciate.

Below is a conceptual Python representation of how packet encapsulation logic functions, mimicking the behavior of a Virtual Tunnel Endpoint (VTEP). This script utilizes Socket Programming concepts to demonstrate header construction.

import struct

import socket

def create_vxlan_packet(inner_eth_frame, vni):

"""

Conceptual demonstration of VXLAN Encapsulation.

Args:

inner_eth_frame (bytes): The original Layer 2 frame.

vni (int): VXLAN Network Identifier (24-bit).

Returns:

bytes: The encapsulated UDP payload.

"""

# VXLAN Header Format:

# Flags (8 bits) | Reserved (24 bits) | VNI (24 bits) | Reserved (8 bits)

# Flags: 0x08 indicates the VNI is valid (I flag set)

flags = 0x08

# Pack the header

# !B3s3sB translates to:

# B: unsigned char (1 byte) -> Flags

# 3s: 3 bytes -> Reserved

# 3s: 3 bytes -> VNI (We need to manipulate bits to fit 24-bit int into bytes)

# B: unsigned char (1 byte) -> Reserved

# Convert VNI integer to 3 bytes

vni_bytes = vni.to_bytes(3, byteorder='big')

vxlan_header = struct.pack('!B3s3sB', flags, b'\x00\x00\x00', vni_bytes, 0x00)

# The full payload is the Header + Original Frame

return vxlan_header + inner_eth_frame

# Example Usage

original_frame = b'\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\x00\x11\x22\x33\x44\x55\x08\x00' + b'Payload Data'

vni_id = 1005

encapsulated_packet = create_vxlan_packet(original_frame, vni_id)

print(f"Original Size: {len(original_frame)} bytes")

print(f"Encapsulated Size: {len(encapsulated_packet)} bytes")

print(f"Hex Dump: {encapsulated_packet.hex()}")This code highlights the overhead introduced by virtualization. The Network Performance implications of this overhead (specifically regarding MTU size) will be discussed later. Understanding these byte-level manipulations is key for Network Development and Protocol Implementation.

Implementation: Linux Namespaces and Virtual Interfaces

At the heart of containerization (Docker, Kubernetes) lies the Linux kernel feature known as Network Namespaces (`netns`). A network namespace provides a completely isolated network stack: its own routing table, firewall rules (iptables), and network devices. This is the bedrock of System Administration for modern cloud infrastructure.

Apple TV 4K with remote – New Design Amlogic S905Y4 XS97 ULTRA STICK Remote Control Upgrade …

Virtual Ethernet (veth) Pairs

To connect a namespace to the outside world or another namespace, we use veth pairs. Think of a veth pair as a virtual Network Cable connecting two endpoints. One end sits inside the container (namespace), and the other sits on the host, usually plugged into a virtual bridge (like `docker0` or OVS).

For a Network Engineer troubleshooting Kubernetes networking, knowing how to manually manipulate these namespaces is a superpower. The following Bash script demonstrates how to create two namespaces and connect them, simulating a simple Network Design on a single Linux host.

#!/bin/bash

# Ensure script is run with root privileges

if [[ $EUID -ne 0 ]]; then

echo "This script must be run as root"

exit 1

fi

echo "Creating Network Namespaces..."

# Create two isolated namespaces (Red and Blue)

ip netns add ns-red

ip netns add ns-blue

echo "Creating veth cable..."

# Create a veth pair: veth-red <-> veth-blue

ip link add veth-red type veth peer name veth-blue

echo "Plugging cables into namespaces..."

# Move interfaces into their respective namespaces

ip link set veth-red netns ns-red

ip link set veth-blue netns ns-blue

echo "Configuring IP Addresses (CIDR)..."

# Assign IP addresses within the namespaces

# We are using private subnets (IPv4)

ip netns exec ns-red ip addr add 10.1.1.1/24 dev veth-red

ip netns exec ns-blue ip addr add 10.1.1.2/24 dev veth-blue

echo "Bringing interfaces UP..."

# Activate the loopback and veth interfaces

ip netns exec ns-red ip link set lo up

ip netns exec ns-red ip link set veth-red up

ip netns exec ns-blue ip link set lo up

ip netns exec ns-blue ip link set veth-blue up

echo "Testing Connectivity..."

# Ping from Red to Blue

ip netns exec ns-red ping -c 3 10.1.1.2

# Clean up (Optional)

# ip netns del ns-red

# ip netns del ns-blueThis script uses standard Network Commands to build a functional topology. It touches on Subnetting, CIDR notation, and interface management. In a real-world scenario, a CNI (Container Network Interface) plugin would handle this Network Automation via Network APIs, but the underlying kernel mechanics remain identical.

Advanced Techniques: Programmable Data Planes and Analysis

Moving beyond basic namespaces, advanced Network Virtualization involves programmable data planes. Tools like Open vSwitch (OVS) and eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) allow for complex packet processing logic without modifying kernel source code. This is essential for implementing Load Balancing, Firewalls, and advanced Network Security policies at the edge.

Analyzing Virtual Traffic

When things go wrong in a virtualized network—packet drops, high Latency, or routing loops—standard tools can sometimes fall short. Packet Analysis becomes more complex because of encapsulation. You might capture traffic on the physical interface and see only UDP packets (the outer VXLAN layer), obscuring the inner HTTP or database traffic.

Using Python with Network Libraries like Scapy allows us to craft specific packets to test firewall rules or dissect captured traffic to verify VXLAN VNI tags. This is a critical skill for Network Troubleshooting.

from scapy.all import *

def analyze_vxlan_capture(pcap_file):

"""

Reads a PCAP file and dissects VXLAN packets to inspect inner layers.

Requires Scapy library.

"""

try:

packets = rdpcap(pcap_file)

except FileNotFoundError:

print("File not found.")

return

print(f"Analyzing {len(packets)} packets...")

for pkt in packets:

# Check if packet has UDP layer and destination port 4789 (Standard VXLAN)

if pkt.haslayer(UDP) and pkt[UDP].dport == 4789:

print("\n[+] VXLAN Packet Detected")

# VXLAN is typically implemented in Scapy as a layer

# If standard dissection fails, we might need to force decoding

if pkt.haslayer(VXLAN):

vxlan_layer = pkt[VXLAN]

print(f" VNI: {vxlan_layer.vni}")

# Inspect the inner payload

inner_payload = vxlan_layer.payload

if inner_payload.haslayer(IP):

src_ip = inner_payload[IP].src

dst_ip = inner_payload[IP].dst

print(f" Inner IP Flow: {src_ip} -> {dst_ip}")

if inner_payload.haslayer(TCP):

print(f" Inner Protocol: TCP Port {inner_payload[TCP].dport}")

# To run this, you would need a capture file:

# analyze_vxlan_capture('network_traffic.pcap')This approach is invaluable when debugging Microservices communication issues where a Service Mesh (like Istio or Linkerd) might be obscuring the root cause. It bridges the gap between DevOps Networking and traditional Network Analysis.

Best Practices and Optimization

Implementing network virtualization is not without its challenges. The abstraction layer introduces complexity that can impact Bandwidth and system resources. Here are key best practices to ensure a robust Network Architecture.

Apple TV 4K with remote – Apple TV 4K 1st Gen 32GB (A1842) + Siri Remote – Gadget Geek

1. MTU and Fragmentation

The most common pitfall in overlay networks is the Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU). Because VXLAN adds headers (50 bytes minimum overhead), the inner payload must be smaller than the physical network’s MTU to avoid fragmentation. Fragmentation kills Network Performance.

Tip: If your physical network MTU is 1500 (standard Ethernet), configure your virtual interfaces (overlay) to 1450 bytes. If you have control over the physical network (Jumbo Frames), increase the physical MTU to 9000 to accommodate the overhead easily.

2. Security and Micro-segmentation

Virtualization enables Zero Trust security models. Unlike physical firewalls which protect the perimeter, virtual networks allow for micro-segmentation. Use Network Policies (in Kubernetes) or Security Groups (in AWS/Cloud) to restrict traffic between specific workloads. Do not rely solely on the NAT gateway; secure the East-West traffic.

3. Monitoring and Automation

Apple TV 4K with remote – Apple TV 4K iPhone X Television, Apple TV transparent background …

Manual configuration is error-prone. Leverage Network Automation tools like Ansible, Terraform, or custom REST API integrations to manage network state. For monitoring, standard SNMP is often insufficient. Use Prometheus exporters or modern observability platforms to track metrics like dropped packets on virtual interfaces.

Below is a Go snippet, relevant for those working in cloud-native environments, to check interface statistics, which is a common task in writing custom Network Monitoring exporters.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"net"

"os"

)

// Simple utility to check interface MTU and Status

func main() {

interfaces, err := net.Interfaces()

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("Error fetching interfaces: %v\n", err)

os.Exit(1)

}

fmt.Println("--- Network Interface Status ---")

for _, iface := range interfaces {

// Filter for potential virtual interfaces or bridges

fmt.Printf("Name: %s\n", iface.Name)

fmt.Printf(" MTU: %d\n", iface.MTU)

fmt.Printf(" Flags: %v\n", iface.Flags)

// Check if interface is up

if iface.Flags&net.FlagUp != 0 {

fmt.Println(" Status: UP")

} else {

fmt.Println(" Status: DOWN")

}

addrs, _ := iface.Addrs()

for _, addr := range addrs {

fmt.Printf(" Address: %s\n", addr.String())

}

fmt.Println("--------------------------------")

}

}Conclusion

Network Virtualization has fundamentally transformed how we design, deploy, and secure infrastructure. From the basic isolation of Linux namespaces to the complex overlay architectures of VXLAN spanning global data centers, the abstraction of the network layer is the enabler of the modern cloud.

For the Tech Travel enthusiast working remotely or the enterprise System Administration team, the principles remain the same: encapsulate, isolate, and automate. As we move toward Edge Computing and increasingly complex CDN architectures, the line between software and hardware will continue to blur. Mastering these protocols, Network Tools like Wireshark and Scapy, and the underlying code that drives them, is essential for anyone looking to stay ahead in the field of digital infrastructure.

Whether you are debugging a DNS Protocol issue in a container or architecting a global HTTPS Protocol load balancer, remember that the virtual network is only as robust as the configuration and understanding of the engineer behind it. Continue experimenting with the code examples provided, dive deep into packet analysis, and embrace the software-defined future.