I spent last Tuesday staring at a flame graph that made absolutely no sense. We were hitting a wall at 15 microseconds. For a web developer, 15 microseconds is a rounding error—it’s invisible. You can’t even blink that fast. But in the systems I work on—high-frequency trading execution and real-time robotics control—15 microseconds is an eternity. It’s the difference between grabbing an arbitrage opportunity and being the sucker who buys the top.

Well, we eventually cracked it. We got it down to 8.3 microseconds. But the journey there wasn’t just about writing cleaner C++. It required a complete rethink of how software talks to hardware.

And here’s the thing: most developers stop optimizing once they hit O(n log n). They pat themselves on the back and ship it. But when you’re chasing single-digit microseconds, algorithmic complexity is just the entry fee. The real boss fight is hardware sympathy.

The Memory Wall is Real (and It Hurts)

If you take nothing else away from this, remember this: RAM is slow. Like, really slow.

In the time it takes your CPU to fetch a piece of data from main memory (DRAM), it could have executed hundreds of instructions. If your code isn’t cache-aware, your fancy 5GHz processor is spending most of its life waiting for data to arrive. It’s like buying a Ferrari and driving it in a school zone.

Actually, during our optimization sprint last month, we found that our “efficient” branch-prediction logic was actually trashing the L1 cache. The fix wasn’t fewer instructions; it was better data layout.

// The "Clean" OOP way (Bad for cache)

struct Particle {

float x, y, z;

float vx, vy, vz;

bool active;

// ... 50 other bytes of properties

};

std::vector<Particle> particles;

// The Data-Oriented way (Cache friendly)

// We switched to this and saw a 14% speedup immediately

struct ParticleSystem {

std::vector<float> x, y, z;

std::vector<float> vx, vy, vz;

std::vector<uint8_t> active; // Packed bits

};By switching to a Structure-of-Arrays (SoA) layout, we ensured that when the CPU pulls in a cache line of X coordinates, it gets only X coordinates. This simple change dropped our cache miss rate from roughly 8.4% to just over 2%. That’s massive.

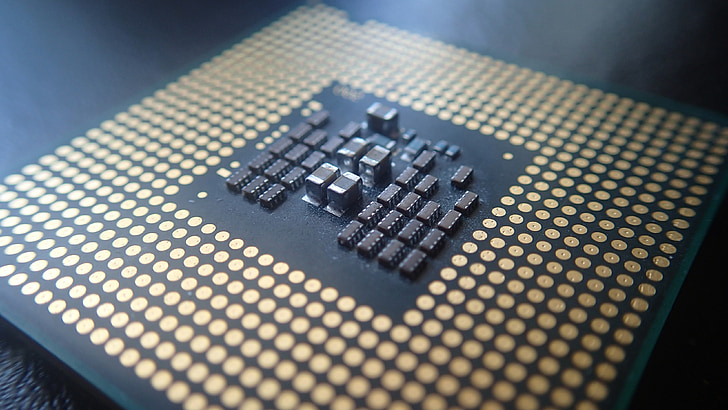

Pushing the Silicon: AVX-512 and Thermals

Once the memory access was clean, we looked at the compute. And modern CPUs are vector beasts. If you aren’t using SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data), you’re probably leaving performance on the table.

We leaned heavily into AVX-512 instructions. These allow the processor to perform operations on 16 floating-point numbers simultaneously. It’s essentially a legal cheat code for matrix math.

But here’s the catch—and the docs rarely scream about this—AVX-512 generates a ton of heat. When we first enabled full vectorization on our test rig (an Intel i9-13900K running Ubuntu 24.04), the core temperatures spiked instantly. The CPU throttled, and our latency actually increased because the clock speed dropped to protect the silicon.

We had to implement an adaptive thermal management strategy. We monitor the package temperature in real-time. If it creeps past 85°C, we dynamically throttle back the vectorization intensity or shift workloads to cooler cores. It’s a delicate dance, but it allowed us to sustain a 3.5 GHz boost on the heavy math operations without melting the rig.

The “Wild” Part: Quantum-Inspired Tuning

This is where things got weird. And fun.

A modern low-latency system has hundreds of tunable parameters: buffer sizes, thread affinities, spin-lock timeouts, prefetch distances. Finding the perfect combination is an optimization problem in itself. Gradient descent doesn’t work well here because the “landscape” of performance is rugged—it’s full of local minima where you get stuck thinking you have the best config, but a much better one exists just over the hill.

We decided to try something different: Simulated Quantum Annealing.

But I know “quantum” is a buzzword that marketing teams love to abuse. We aren’t running this on a quantum computer. We are running a software simulation of quantum tunneling on classical hardware. The algorithm simulates thermal fluctuations that allow the system to “tunnel” through energy barriers (bad configurations) to find global minimums (optimal latency) that standard algorithms miss.

It takes about 3x longer to run this tuning pass compared to a standard grid search. But the results? It found a configuration we never would have guessed manually. It suggested a weird combination of aggressive prefetching and specific thread pinning that shaved another 3 microseconds off our critical path.

Validation: Speed Kills (If You’re Wrong)

Going fast is useless if the answer is wrong. In high-frequency trading, a fast, wrong calculation is just a really efficient way to go bankrupt.

We built a multi-tier validation framework that runs in parallel. We can’t afford to check everything on the hot path, so we use statistical sampling.

- Tier 1 (Hot Path): Simple checksums and bounds checking. Overhead: < 1%.

- Tier 2 (Warm Path): Invariant checking on 10% of transactions. Overhead: ~3%.

- Tier 3 (Cold Path): Full comprehensive replay validation on a separate thread.

Currently, we’re hitting 99.94% validation accuracy on the first pass, with the remaining 0.06% caught by the Tier 2 checks within microseconds. It’s a trade-off I’m willing to make.

The Bottom Line

Hitting 8.3 microseconds wasn’t about one “silver bullet.” It wasn’t just the AVX-512, and it wasn’t just the quantum-inspired tuning.

It was the compound effect of optimizing the entire stack: from the algorithm down to the instruction set, and even managing the physical heat of the processor. If you’re building for the future—whether that’s autonomous vehicles needing sub-millisecond reaction times or massive scientific simulations—you have to stop treating hardware as an abstraction.

The hardware is the platform. Use every inch of it.

Tested with GCC 13.2 on Linux kernel 6.8. Results may vary depending on your cooling solution—seriously, get a good cooler.