In the vast, interconnected world of computer networking, few protocols are as fundamental and ubiquitous as the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP). It is the bedrock of the World Wide Web, the invisible engine that powers every website you visit, every API call your application makes, and every cat video you stream. For developers, network engineers, and system administrators, a deep understanding of HTTP isn’t just beneficial—it’s essential for building robust, secure, and performant applications.

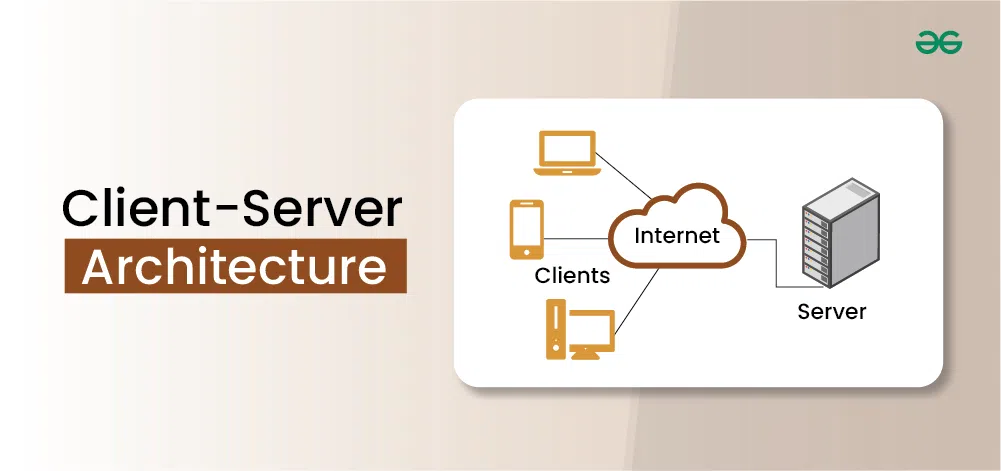

At its core, HTTP is an application-layer protocol within the TCP/IP suite, designed for distributed, collaborative, and hypermedia information systems. It operates on a client-server model, where a client (typically a web browser or an application) sends a request to a server, which then processes it and sends back a response. This simple, stateless request-response cycle is the foundation upon which the modern internet is built. This article will dissect the anatomy of HTTP, explore its methods and status codes, trace its evolution, and provide practical best practices for leveraging its full potential in modern network architecture and API design.

The Anatomy of an HTTP Request/Response Cycle

Every interaction on the web begins with an HTTP request and ends with an HTTP response. Understanding the structure of these messages is the first step toward mastering the protocol. They are text-based messages, meticulously formatted to be understood by both clients and servers.

The Client’s Request

An HTTP request consists of three main parts: the request line, headers, and an optional message body. Let’s break down a typical request to fetch a user’s profile from an API.

- Request Line: This is the first line and contains the HTTP method (e.g., GET, POST), the Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) of the resource, and the HTTP protocol version. Example:

GET /api/users/123 HTTP/1.1 - Headers: These are key-value pairs that provide additional information about the request or the client. Common headers include

Host(the domain name of the server),User-Agent(identifies the client software), andAccept(specifies the media types the client can handle). - Message Body: This is an optional part used for requests that need to send data to the server, such as a POST or PUT request. For a GET request, the body is typically empty.

Here’s how you can make a simple GET request using Python’s popular requests library, a staple in network programming and web scraping.

import requests

import json

# Define the API endpoint

url = "https://api.example.com/data/1"

# Define headers

headers = {

'User-Agent': 'MyCoolApp/1.0',

'Accept': 'application/json'

}

try:

# Send the GET request

response = requests.get(url, headers=headers)

# Raise an exception for bad status codes (4xx or 5xx)

response.raise_for_status()

# Parse the JSON response

data = response.json()

print("Successfully fetched data:")

print(json.dumps(data, indent=2))

except requests.exceptions.HTTPError as http_err:

print(f"HTTP error occurred: {http_err}")

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as err:

print(f"An error occurred: {err}")The Server’s Response

After receiving and processing the request, the server sends back an HTTP response. Like the request, it has a specific structure: the status line, headers, and the message body.

- Status Line: This line includes the HTTP protocol version, a numeric status code, and a human-readable reason phrase. Example:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK - Headers: Response headers provide metadata about the response. Key headers include

Content-Type(the media type of the response body, e.g.,application/json),Content-Length(the size of the body in bytes), andDate. - Message Body: This contains the actual resource or data requested by the client, such as the HTML for a webpage or the JSON data from an API.

HTTP Methods and Status Codes: The Language of the Web

If the request/response cycle is the grammar of HTTP, then methods and status codes are its vocabulary. They define the actions to be performed and the outcomes of those actions, forming the core logic of web services and REST APIs.

Common HTTP Methods (Verbs)

HTTP methods, often called “verbs,” indicate the desired action for a given resource.

- GET: Retrieves a representation of the specified resource. It should be safe and idempotent (making the same request multiple times has the same effect as a single request).

- POST: Submits an entity to the specified resource, often causing a change in state or side effects on the server. For example, creating a new user or posting a comment.

- PUT: Replaces the entire target resource with the request payload. It is idempotent.

- DELETE: Deletes the specified resource. It is also idempotent.

- PATCH: Applies partial modifications to a resource.

Here is an example of creating a new resource using a POST request with JavaScript’s axios library, a common tool for front-end and Node.js development.

const axios = require('axios');

async function createTravelBooking() {

const bookingData = {

destination: "Kyoto, Japan",

travelerName: "Jane Doe",

departureDate: "2024-10-26"

};

try {

const response = await axios.post('https://api.travelservice.com/bookings', bookingData, {

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/json',

'Authorization': 'Bearer your_api_token_here'

}

});

console.log('Booking created successfully!');

console.log('Status Code:', response.status); // Should be 201

console.log('Response Data:', response.data);

} catch (error) {

console.error('Error creating booking:', error.response ? error.response.data : error.message);

}

}

createTravelBooking();Understanding Status Codes

Status codes are the server’s way of communicating the result of the client’s request. They are grouped into five classes:

- 1xx (Informational): The request was received, continuing process.

- 2xx (Successful): The request was successfully received, understood, and accepted (e.g.,

200 OK,201 Created). - 3xx (Redirection): Further action needs to be taken to complete the request (e.g.,

301 Moved Permanently). - 4xx (Client Error): The request contains bad syntax or cannot be fulfilled (e.g.,

400 Bad Request,401 Unauthorized,404 Not Found). - 5xx (Server Error): The server failed to fulfill a valid request (e.g.,

500 Internal Server Error,503 Service Unavailable).

Interestingly, the 402 Payment Required status code has existed since the early days of HTTP but was reserved for future use. Recently, it has seen a resurgence in experimental protocols aiming to create a native payment layer for the web, enabling micropayments for content or API usage without traditional ads or subscriptions. This highlights HTTP’s extensibility and its capacity to adapt to new paradigms like the creator and AI agent economies.

Here’s a simple Node.js server using the Express framework that demonstrates how to handle different requests and return appropriate status codes.

const express = require('express');

const app = express();

app.use(express.json());

const data = { id: 1, name: "Sample Resource" };

// Handle GET request

app.get('/resource', (req, res) => {

res.status(200).json(data);

});

// Handle POST request

app.post('/resource', (req, res) => {

const newItem = req.body;

if (!newItem || !newItem.name) {

// Return a client error if data is missing

return res.status(400).json({ error: 'Name is required' });

}

console.log('Created new item:', newItem);

// Respond with 201 Created

res.status(201).json({ message: 'Resource created', data: newItem });

});

// Handle a route that doesn't exist

app.use((req, res) => {

res.status(404).send("Sorry, can't find that!");

});

const PORT = 3000;

app.listen(PORT, () => {

console.log(`Server is running on http://localhost:${PORT}`);

});Evolution and Security: From HTTP/1.1 to HTTP/3 and HTTPS

The web’s demands have grown exponentially, requiring the HTTP protocol to evolve to improve network performance and security. This evolution is a key topic in network design and for any DevOps networking professional.

The Performance Leap: HTTP/2 and HTTP/3

For many years, HTTP/1.1 was the standard. While revolutionary, it had limitations, most notably “head-of-line blocking,” where a single slow request could hold up all subsequent requests over the same TCP connection. This increased latency and underutilized available bandwidth.

HTTP/2, standardized in 2015, addressed this by introducing multiplexing. It allows multiple requests and responses to be sent concurrently over a single TCP connection, eliminating head-of-line blocking at the application layer. It also added features like header compression (HPACK) and server push.

HTTP/3 represents the next frontier. It abandons TCP in favor of a new transport protocol called QUIC, which runs over UDP. QUIC integrates the TLS handshake and provides streams at the transport layer, solving the head-of-line blocking problem even more effectively than HTTP/2. This is crucial for mobile users and anyone on unreliable networks, a common scenario for a digital nomad or frequent traveler.

Securing the Connection with HTTPS

HTTP messages are, by default, sent in plaintext, making them vulnerable to eavesdropping and tampering. HTTPS (HTTP Secure) solves this by layering HTTP on top of the Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol (formerly SSL). TLS provides three key security benefits:

- Encryption: Protects the data from being read by third parties.

- Integrity: Ensures the data has not been altered in transit.

- Authentication: Verifies the identity of the server you are communicating with, preventing “man-in-the-middle” attacks.

Today, HTTPS is the standard for all web traffic. Modern browsers actively warn users when they visit non-HTTPS sites, and it’s a critical component of network security and API security.

Best Practices and Modern Tooling

Effectively using HTTP requires adherence to best practices and familiarity with modern tools for development and network troubleshooting.

API Design and Idempotency

When designing a REST API, use HTTP methods semantically. Use GET for retrieval, POST for creation, PUT for replacement, and DELETE for removal. A critical concept is idempotency. An operation is idempotent if making it multiple times produces the same result as making it once. GET, PUT, and DELETE should always be idempotent. This is vital for building resilient systems where network requests might be retried automatically.

Performance Optimization

To improve network performance, leverage HTTP’s built-in features:

- Caching: Use headers like

Cache-Control,Expires, andETagto instruct clients and intermediate proxies (like a CDN) to cache responses, reducing server load and latency. - Compression: Use Gzip or Brotli compression (indicated by the

Content-Encodingheader) to reduce the size of response bodies, saving bandwidth. - Content Delivery Networks (CDN): A CDN caches content at edge computing locations closer to users, dramatically reducing latency for a global audience.

Troubleshooting and Analysis

Every network engineer and developer needs a solid toolkit for debugging HTTP issues.

- Browser DevTools: The “Network” tab is invaluable for inspecting requests and responses directly in your browser.

- cURL: A command-line tool for making raw HTTP requests. It’s perfect for quick API testing and scripting.

- Postman/Insomnia: GUI tools that provide a powerful interface for designing, testing, and documenting APIs.

- Wireshark: A powerful packet analysis tool that lets you inspect network traffic at the lowest level, essential for deep network troubleshooting.

Here’s a simple curl command to test an API endpoint, including a custom header.

# Make a GET request to an API endpoint with a custom header

# -v (verbose) shows the request and response headers

# -H adds a header

curl -v -H "Authorization: Bearer mysecrettoken" "https://api.example.com/v1/profile"Conclusion

From its humble beginnings as a simple protocol for fetching hypertext documents, HTTP has evolved into the sophisticated, powerful backbone of the modern internet. It underpins everything from simple websites to complex microservices architectures, cloud networking, and the burgeoning API economy. Its stateless nature, combined with a rich set of methods, status codes, and headers, provides a flexible framework for communication across the open web.

As we move into an era of AI-to-AI communication, decentralized applications, and new monetization models, the principles of HTTP will remain more relevant than ever. By mastering its request-response cycle, understanding its evolution to HTTP/3, and implementing security and performance best practices, developers and network professionals can build the next generation of resilient, efficient, and secure applications. The unseen engine of the web will continue to power our digital future.